ProSocial - Common Commons

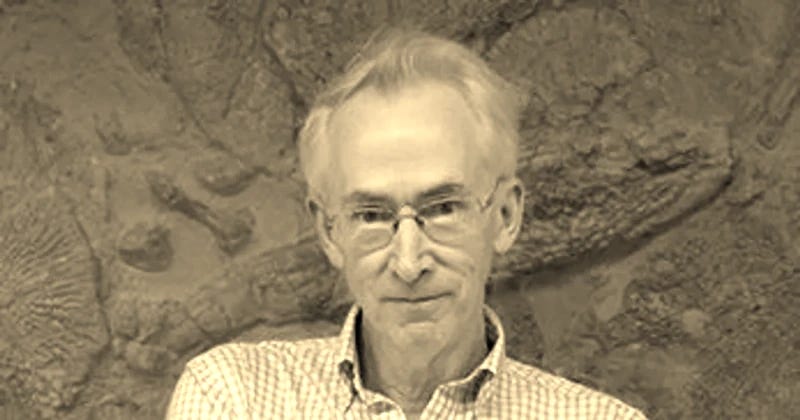

The Commons of Care - in gratitude to David Sloan Wilson

I’ve been in long, generous conversation with David Sloan Wilson these past months, and I keep finding myself both moved and steadied. David has spent a lifetime showing how cooperation actually survives in the wild, not as a fairy tale but as something that needs the right conditions and the right rules.

He shows when it works, why it fails, and (crucially) what special conditions are needed for groups to function as wholes. Hearing him name the “special conditions” for group-level function felt like someone handing me the missing wrench for work I’ve been doing with Grassroots Economics in villages, settlements, and federations of small groups for years.

Incredibly - economic policy often still reaches for the old “tragedy of the commons” tale (Hardin, 1968) - as if shared resources inevitably collapse without privatization or state command. Elinor Ostrom’s fieldwork punctured that inevitability. She gave evidence that tragedy is mostly unregulated open access, not a well-governed commons.

A real commons is said to have a resource, a community of commoners, and their own rules about use and stewardship. We’re comfortable applying that to water or wood. Speaking with David has helped me to apply it, more honestly, to what we see every day: trust, attention, kinship, belonging, safety, empathy. In Ostrom’s language, these are rivalrous in one sense (time and attention are finite) and renewable in another (good practice grows capacity). Treating care as a stewarded resource (instead of a vague vibe) makes this work into a science.

That frame has helped me say something simple I’ve been circling:

the most common commons isn’t a forest or a fishery. It’s care.

Said more accurately : I believe the most common form of the commons is not biophysical (e.g., forests or fisheries) or the governance of firms/cooperatives but socio-relational: the shared, collectively governed capacity for care.

I think that care is the modal (common) commons on three fronts: prevalence (it is the most frequently instantiated, everyday form of commoning), importance (it is normatively foundational for human flourishing), and causal priority (it underwrites the viability of other commons by enabling trust, coordination, and rule maintenance).

A quick thanks here to my friends from Mustard Seed and especially Bela Hatvany for his constant reminders and emphasis on the Economy of Care.

Does care meet the commons test? In practice, yes, when a healthy group can name what care looks like here, knows who can ask and who can offer, writes and revises its own norms, witnesses commitments and follow-through without shame, resolves friction quickly and humanely, is recognized in its wider context, and nests with other circles when scale or specialization is needed.

If you can answer those with a “yes,” you’re not just feeling care - you’re stewarding it as a commons.

This again, is where David’s work on ProSocial has been a gift. He takes Ostrom’s Core Design Principles and brings them inside the group: not just the outer architecture of rules, but the inner skills that let rules breathe.

David co-founded ProSocial World which pairs the design principles of Ostrom with practical skills from Acceptance & Commitment Training (ACT) - values clarified together, do-able commitments, present-moment attention, making room for difficult feelings, seeing thoughts as thoughts, and practicing perspective from “we,” not just “me.” It sounds simple, but it’s the difference between a charter that lives and a charter on paper. Add psychological safety (the felt permission to speak up, admit mistakes, ask for help) and a group can adapt its own rules without tearing itself apart. That is the “special condition” most plans forget.

Around that inner grammar of care, the outer governance has to be legible and light - we can begin to map out (echo locate) a whole series of protocls.

Consent-based decision methods keep authority shared and visible.

Clear roles and agreements say who does what without freezing the living tissue of relationship.

Restorative practice and deep-democracy lineages give us ways to meet tension without exile: listening as a civic act, objection as information.

Somatic disciplines—breathwork, tai chi, trauma-informed movement—return us to the ground where regulation begins, so bodies can settle enough to choose.

Ecological design teaches reciprocity by design, so our arrangements fit their place and nest well in larger patterns.

If this sounds like a protocol stack for an intangible commons, that’s exactly how I read David Sloan Wilson’s work: protocols that make cooperation selectable at the group level.

On the economic layer, we’ve been mapping out and learning Commitment Pooling Protocol to keep the commons of care visible without commodifying it. People (or group agents) make named commitments (offers and requests) with explicit consent and exit. We keep relational memory through simple attestations (“who showed up, for what, when”). We follow parity guides (relative value indices) to avoid silent inequities (an hour of transport can stand with an hour of childcare). We set gentle credit limits on pull from the commons, with clear emergency overrides, so generosity stays renewable. We add match-making rhythm to route requests and close the loop with witnessed completion. This is not trying to measure love … it records promises kept.

Because intangibles spill and blur, boundaries in a care commons are not fences but membranes for curations: who belongs here, what “care” means in this circle, what support we offer and what we don’t. Monitoring is witnessing and relational memory, not surveillance. Sanctions begin as restoration (check-ins, support plans, pauses) … before any access limits.

And because care labor has been unevenly loaded along gendered and racialized lines, equity isn’t a footnote: rotate burdens, check parity, build rest windows and no-fault pauses. Privacy matters, too: collect the minimum, by consent, with clear retention and access rules. These are not niceties …. they’re the guardrails that keep a care commons regenerative rather than extractive.

(you will have noticed in this substack journal, me looking at various protocols).

Testing Protocols

These protocols all aim to do two things:

Cut down on selfish behavior inside the group by keeping an eye on commitments, fixing problems first through support, and preventing any one person from holding too much power.

Reward the whole group (network of groups) for working well together by making it easy to return help and by linking circles through simple agreements.

We can test if they’re working if groups that use these protocol more consistently get more promises kept and don’t dump most of the care work on the same few people.

Learning

Underneath all of this is a posture I keep learning from David’s work as intelligence reframed for living systems. Our capacity to sense → make meaning → care → commit → coordinate → learn, then update the rules.

Read that way, intelligence is a meta-protocol that routes attention and trust so life can keep flourishing. I am grateful for David and ProSocial for giving names and practices for this loop.

And when rupture comes (as it has and will) repair starts with agreement; with purpose (“to learn, not to win”); with humane containers (turn-taking, aftercare). Low-cost conflict resolution (grace).

One last scale point David and I discuss keeps me honest about: a “group” in our world is rarely a single circle. It’s a network of overlapping pools - neighborhoods, care circles, learning groups, food production, savings, watershed - held together by consented agreements. That overlap defines the community/commons, and that’s where selection for harmony can be made real - across physical scales (household to watershed), social scales (crew to federation), and time scales (weeks to seasons to years). Our protocols, and our measures, need to match those rhythms.

If you’ve followed Grassroots Economics, you know we lean on rotating labor associations and federations of savings and loan groups, because they’re familiar, sturdy, and humbly amazing. In this lens, I see them even more clearly as made up of cells (individual agents) as well as organs in a larger body. The work is to keep those cells and organs healthy, help them talk to each other, and let them split gracefully when they need to. That’s a living system, not a machine.

So when I being to name a “Commons of Care,” I mean something precise and doable, and I hear David’s fingerprints all over it: don’t assume harmony; install the conditions that make it possible. If a group can name its care, choose together, remember together, repair together, and learn together, it’s already governing care as a commons. Families do this in their best hours; so do choirs, teams, gardens, congregations, block clubs, co-ops, and mutual-aid rings.

Our job isn’t to mystify it or worship it. It’s to keep practicing - and to keep the protocols light, human, and revisable, so the living thing can keep living.

I’m grateful for the chance to compare notes with David. He brings the intellectual high ground; we bring the dirt under the fingernails. Between us is a shared aim: liberty as a living, adaptive system of voluntary cooperation (agreements people consent to and can revise) scaled from a family table to a watershed.

If that sounds lofty, it’s not. It’s just practice, repeated: attention turned into care; care into commitment; commitment into coordination; coordination into learning; learning back into wiser care.

The rest we’ll keep learning - together.

Here you’ll find a podcast of David and I on these topics:

Right, it goes beyond the biophysical and mere reciprocity among people. I was initially inspired by Davids Wilson's use of Ostrom's Core Design Principle to, refershingly reframe the "conflict negotiation space", as a common resource. Reframing "Care" as a comon pool resource broadens the possibilities even more. Deliberately creating the necessary conditions for it to happen, where it does not emerge spontaneously, and practicing nurturing the Care Commons with a growth mindset to learn how to best steward it in one's particular context, makes for a refreshing compassionate way to intentionally evolve trust and prevent conflict (even de-escalate it) and florish! -- i.e., a timely revival of ancestral wisdom! Thank you for laying out so simply and clearly Will!

“Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary.”