Jesus, Muhammad, and the Path from Household to History

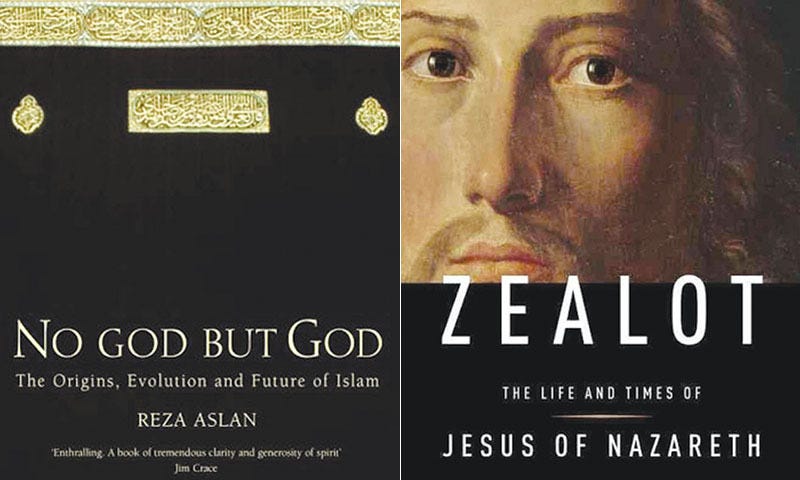

Combined book review of Reza Aslan's Zealot and No God but God

When I finally set Reza Aslan’s books side by side - Zealot, on Jesus of Nazareth, and No god but God, on the Prophet Muhammad - I find myself drawn into a single, long conversation about nearness and reach. Nearness is the warmth of family rooms and dusty roads, the intimacy of those who shared meals and worries and silence with a friend, family member, teacher. Reach is what happens when a message leaves the neighborhood and crosses languages, provinces, and centuries. Both Jesus and Muhammad lived at the meeting point of nearness and reach, and both left communities that learned, sometimes painfully, how to hold memory close while carrying truth far.

These two books are amazing. They really illuminate the life and times of these men in a way no other book has done for me. Reza Aslan does this with great care and study of available knowledge on the subjects. Here are some of my takeaways as I process ….

As Jesus walks into history under the shadow of Rome. Taxes bite, bloody crosses dot the horizons as warnings, and the Temple stands at the heart of a people struggling to honor God while surviving empire. In that world he announces the nearness of God’s reign, gathering a circle of friends, healing, blessing children, challenging hypocrisy, and telling stories that turn power inside out. Whatever one believes about his identity, the public record ends with an unmistakably political sentence: execution by Roman authority (as a rebel against the Roman Empire). Muhammad begins in Mecca, a wealthy marketplace built around a sanctuary and a fragile balance of clan honor and trade. Into that world the Qur’an speaks the fierce mercy of one God who sees the orphan and the widow, asks the comfortable to share what they have, and gives courage to the fearful. Persecution follows, and then migration to Medina, where revelation becomes communal life (treaties, adjudication, prayer, charity, defense).

It matters to me to read and consider aloud what these similarities and differences mean, especially for people of faith (such as my dear friends) who hold these lives sacred. Jesus gathers disciples and crowds, and his power is the authority of a life that heals and a word that finds truth. Muhammad leads a community that must sometimes fight to live, and he returns to Mecca as a leader who, by the witness of Islamic tradition, leans toward mercy and reconciliation. These similar paths help explain why their communities took such shapes when grief and love had to become institutions.

Institutionalizing - Christianity

After Jesus’ death, the small circle in Jerusalem turns first to a kinsman: James, remembered as “the Just,” a figure of quiet authority whose piety and steadiness anchor those who knew Jesus best. The early community remains close to Israel’s scriptures and practices; they are not inventing a religion but testifying that God has moved within their own story. And yet the message refuses to stay local. The Apostle Paul, who never met Jesus in life but recounts a searing vision of the risen Christ, becomes the one who threads the gospel through synagogues and city squares across the Mediterranean. He insists that the good news must be freed to embrace Gentiles (Non-Jews) without demanding a full conversion to Jewish law, and his letters begin to shape the imagination of scattered assemblies. Over time, bishops and councils, creeds and canons, stabilize a faith that must now speak in courts and kitchens across the world. The center of gravity tilts (never wholly, never uncontested) from the kin-held memory of Jerusalem to a portable, universal proclamation.

Institutionalizing - Islam

Islam knows its own version of that delicate tension. From the beginning, the Prophet’s household carries a kind of moral nearness that Muslims across traditions revere. Khadīja, Muhammad’s first wife, is the first believer, a patron and confidante whose trust steadies the fledgling mission. ʿAlī, cousin and son-in-law; Fāṭima, daughter; Ḥasan and Ḥusayn, grandsons—the Ahl al-Bayt, the People of the House—become names that Muslims whisper with love. After Muhammad’s death, leadership of the community passes to companions chosen by consensus; under the caliphs the ummah grows vast, and with growth comes the need for method. Scholars (jurists and hadith experts) undertake the careful labor of collecting the Prophet’s sayings and actions, weighing chains of transmission, reasoning analogically from the Qur’an and example to new questions. In Sunni worlds there is no priesthood, yet the learned become guardians of a shared path. In Shiʿa worlds, the Imams (descendants of the Prophet through Fāṭima and ʿAlī) bear continuing authority, and the martyrdom of Ḥusayn at Karbalāʾ becomes an enduring grammar of conscience against tyranny. Between these ways of holding authority, Sufi paths often trace a spiritual chain back through ʿAlī, marrying love of the Household to an interior schooling in remembrance, so that nearness and reach might reconcile in the heart.

Across these different landscapes, something recognizable keeps surfacing. Both Jesus and Muhammad speak an ethical monotheism that refuses to separate devotion from justice. They call people to prayer and generosity, to fidelity and mercy, to a God who is at once more intimate and more uncompromising than the gods of power. They restore the poor to the center of attention and point out the risk of those who are wealthy and powerful. Their words live along roads, in small rooms where someone is hungry and someone has food. And they do not walk alone. The gospels remember women who traveled with Jesus and funded his work, women who stood near when others fled and were first to proclaim joy in the garden. Islamic memory centers women as well: Khadīja’s patronage, ʿĀʾisha’s keen intellect and legal authority, Fāṭima’s moral weight. Without them (without these rooms of trust) there is no movement to institutionalize.

To compare is not to collapse differences. Many Christians confess the cross and resurrection at the center of their faith; Muslims hold the Qur’an as God’s recitation and Muhammad as His Messenger. Christian scripture is a library formed over time; Islamic scripture is a recited Book, with the Prophet’s example and the vast hadith tradition as its living commentary. Christians navigate empires as minorities for centuries before power ever touches their hands; Muslims must ask, almost immediately, how to live the will of God with borders to defend and taxes to collect. These are not small divergences …. they are the conditions that shaped the textures of spirituality, law, and leadership that followed.

Even so, the kinship between the stories remains instructive to me. In Jerusalem, the memory of Jesus is tenderly held by those who called him brother and teacher; in Medina and Kufa and beyond, the memory of Muhammad is carried by those who shared his home and his hardships. In both traditions, the movement widens beyond what any household can contain. The Apostle Paul’s letters knit communities across seas; the jurists’ methods allow a vast ummah to pray in rhythm and settle disputes without breaking apart. Sometimes nearness and reach strain against each other; sometimes they enrich one another. The friction is not a sign of failure so much as a sign of life. A message worth carrying will inevitably chafe at the limits of its first language and first loyalties.

I really appreciate Reza Aslan writing. I find it very challenging and feel I know so little. Writing about such lives asks for reverence in the best sense: the humility to let each tradition name its own center, the patience to distinguish faith’s confession from a historian’s reconstruction, the discipline to speak carefully where memories are sacred. It helps to remember that both communities invite self-critique from within. Jewish prophets before Jesus speak God’s justice against their own people; the Qur’an itself calls believers to weigh their motives and purify their intentions. If there is a way to honor Jesus and Muhammad together, perhaps it begins by letting their words examine us before we examine them.

What, then, do I carry forward from reading these two stories side by side? I find gratitude for the quiet courage of family and friends who first believed when belief was costly (I really had no idea about these families that Reza Azlan brings to life). I find respect for the unglamorous craft of interpretation (the letters and legal opinions, the sermons and study circles) that made it possible for strangers to pray together and call each other sister, brother, neighbor.

I find a renewed sense that the most durable revolutions are not always the ones that topple thrones, but the ones that change what a household values when no one is watching.

Jesus’ beatitudes and parables, Muhammad’s calls to give alms and break cycles of vengeance - these are not slogans; they are habits of seeing and acting that form people capable of mercy.

As Reza Aslan teach - to hold these lives in a single gaze is not to judge them against each other, but to let them illuminate one another. In one, God’s reign breaks in among the powerless, even as the empire tightens its grip. In the other, God’s guidance becomes the grammar of a community learning to govern without forgetting the orphan.

Both ask us to love beyond kin and also to honor the kin who taught us how to love at all.

Between nearness and reach (between a mother’s kitchen and the public square) something of God’s address to the human heart keeps sounding.

If we can hear that address with the tenderness these traditions teach, our comparisons will not belittle but bless, and our understanding will begin to resemble the truth it seeks.

Thank you for your thoughtful reflection on Jesus and Muhammad, inspired by your reading of Reza Aslan’s work. You touched on many significant themes, particularly the historical contexts and the profound challenges both figures came to address.

Jesus—announced by John the Baptist—came to baptize us with the Spirit of God, presenting Him as the Lamb of God. What a mission! His message calls for an intimate and personal conversion. Paul the Apostle, as you mentioned, played a vital role in carrying Christ’s message to the Gentiles. Interestingly, he was deeply cautious about institutions and consistently advised keeping hierarchies to a bare minimum. In those first Christian communities, property was shared by all—a striking image of solidarity. It would be fascinating to explore implicit Mwerias in early Christian life. Yet Paul was not only an organizer; he was also a mystic, able to say: “I no longer live, but Christ lives in me.” This is what we know as kenosis—the self-emptying that is both mysterious and profoundly beautiful.

The Prophet Muhammad—peace and blessings be upon him—came to affirm the ultimate principle of the Abrahamic tradition: “There is no god but God.” Humanity constantly needs to be reminded of this Truth, since we are naturally inclined toward subtle forms of polytheism. The One is the only true reality, and we exist as part of It. Yet Muhammad’s mission also addressed, from its very beginnings, the concrete question of how societies should be formed and governed. In this respect, his role recalls that of Moses: not only a prophet, but also a lawgiver, a leader, and a nation-builder.

What moves me deeply is that Muhammad himself spoke of Jesus as al-Masīḥ—the Messiah—who is expected to return at the end of times. This points to a profound unity between them. Part of our responsibility, as members of these traditions, is to bring that unity into manifestation.

I believe the shared qualities you identify in both religions reflect this calling: a duty to compare without collapsing distinctions, to understand the grammar of each faith, and to cultivate the common elements that unite us—including, the capacity for self-criticism and renewal.