Composting the Devil's Dung

Franciscan Wisdom and the Future of the Commons

At a time when banks collapse, trust falters, and ecological systems teeter ... it might seem odd to look toward barefoot friars and forest fungi. But perhaps, in their quiet ways, they held the blueprints we’ve lost. I’m blessed to have a final week here in Kenya with Juan Fernando Lucio from Colombia. Muchas gracias for the deep conversations and inspiration.

As I learn more about Franciscan Econmics, there’s something astonishing (almost mythic) in the integrity of the early Franciscans. These were not people gesturing at simplicity. They were radically committed to a life that mirrored the humility of Christ, barefoot and uncluttered, drawn to the edges of wealth and power. For them, money wasn’t just dangerous - it was spiritually radioactive. Saint Francis called it “the dung of the devil.” And indeed, they believed it left a residue, a smell, a heaviness in the soul. Touching coins was not a neutral act. It bent the heart. It fed illusions of control. It violated trust in divine and communal providence.

And yet, people must eat. A friar (priest) might own nothing, but his sandals still wore out. So what then? If one must not touch the dung of the devil… how, still, to live?

The answer emerged as a strange and brilliant workaround - the procurator.

The word procurator comes from the Latin pro ("for") and curare ("to care for"). A procurator was someone who would handle finances on your behalf - a carer, not an owner. In the Franciscan world, procurators were lay people, not friars, who received money, turned it into useful goods, and passed it on. They stood between the friars and the world of transaction, acting like ethical membranes between sacred vow and worldly need. They didn’t enrich themselves. They translated - from gold to bread, from danger to service.

This wasn’t just a legal loophole. It was a theological innovation. A practical mysticism. The procurator was not merely a workaround for poverty. They were a vessel of moral coherence, allowing the friars to remain true to their vow while not starving in a material world.

It is here - in this curious and holy role - that we glimpse a deep ecological metaphor. For the forest, too, has procurators.

Mycorrhizal fungi, those vast underground networks connecting tree to tree, perform an uncannily similar function. They receive excess sugars from older trees, digest raw minerals, and deliver nutrients to saplings or struggling roots. They are non-possessive agents of exchange, operating by trust and relational memory. They serve the ecosystem, ensuring its health and mutual nourishment.

Yet as wondrous as the fungal model may be, and as noble as the Franciscan solution appears, we must also approach the role of the procurator with caution. None of these intermediaries are neutral – especially when these roles are held by humans. How do we stay deeply ethical? How do we refuse accumulation? How do we preserve trust in a complex world?

…. we all have needed procurators. We all, at some point, rely on someone else to carry a burden we cannot touch. Whether it's a friend navigating bureaucracy, a treasurer managing group funds, or a delegate acting in our name …. these are essential roles in any collective life.

But what happens when that steward becomes a bottleneck? When they (or we) begin to own the role instead of serve it? History gives us both sacred examples… and tragic warnings.

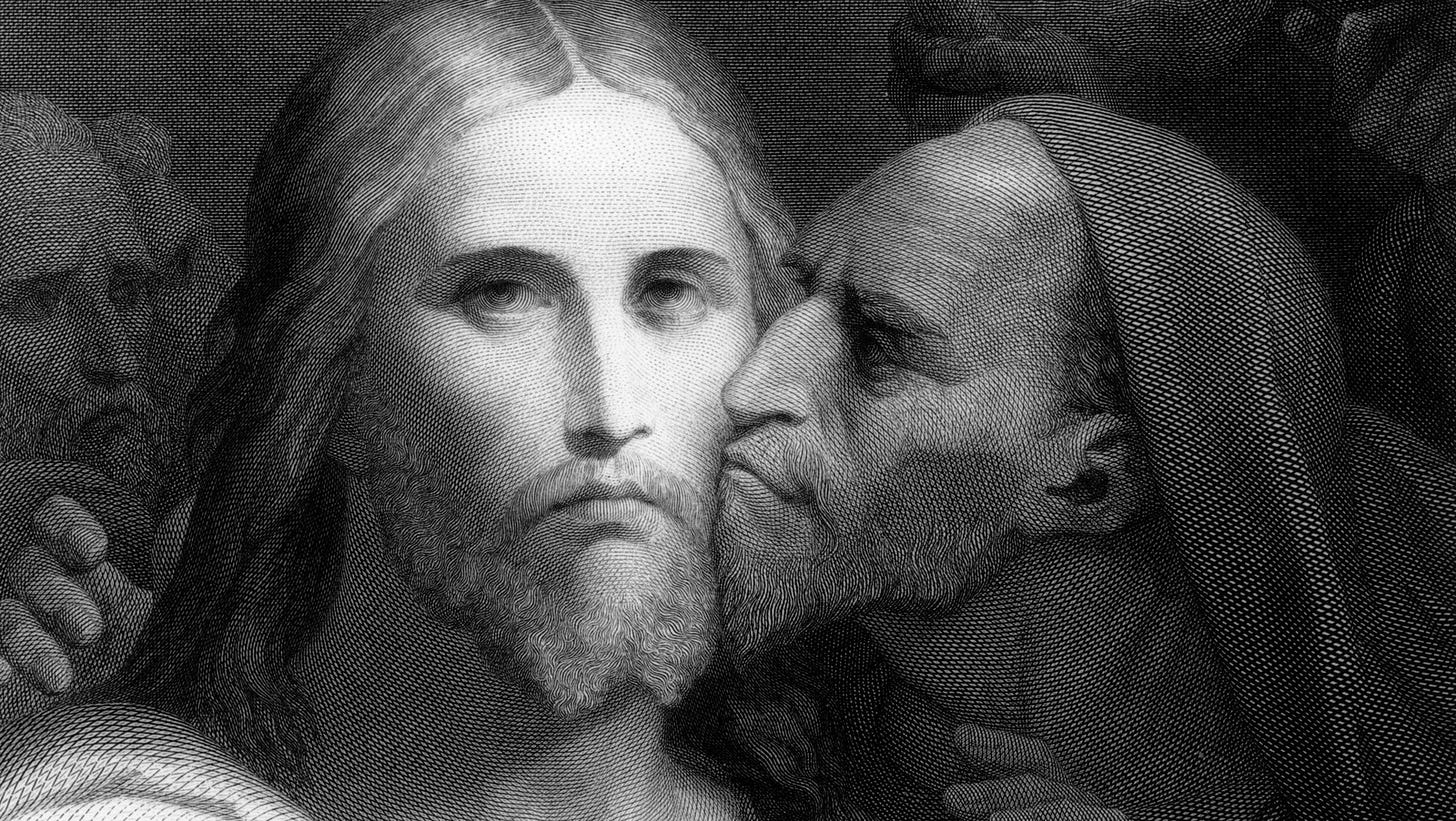

In the Christian tradition, we might ask: Was Judas the procurator of Jesus? According to the Gospel of John, Judas Iscariot was the keeper of the common purse (the treasurer for Jesus and the disciples).

He carried the bag.

He managed the group's material needs.

But over time, he began to identify with the contents of the purse rather than its purpose. The moment came when he sold his role (and his teacher) for thirty pieces of silver (the standard price for a slave at the time).

Whether seen as villain or warning, Judas’s fall reminds us what happens when trust becomes transaction, and service becomes possession

The danger was not in money alone. It was in possessive stewardship ... when a procurator ceases to act for others and begins to act in place of them, obscuring the flow of care with the shadow of control.

And so it is with modern life. Banks, brokers, institutional funders (these are the remaining procurators of our rapidly changing era). They digest and convert money on behalf of others. But too often, they do so without transparency, without limits, and without accountability. The role that should serve becomes a gatekeeper. The nutrient becomes a tax.

But what if the role of the procurator was no longer a person (or even a company) but a shared protocol?

This is where Commitment Pooling offers a path forward.

Inspired by ancestral forms of collective labor like the Minga of Colombia, the Mweria of Kenya, the fa’alavelave of Polynesia, and the gifting circles of so many traditions, Commitment Pooling codify the functional mechanisms of procuration (curation, valuation, limitation, and exchange) and renders it public, transparent, accountable and cooperative.

In a Commitment Pool:

Curation: Communities choose together which kinds of commitments enter the pool (labor, time, care, money). (For example, a community pool might hold gift cards, work pledges, and care hours — redeemable among neighbors who contribute.)

Valuation: Agreements are made about how to recognize and redeem those contributions through collective relevance (able to diverge from market forces).

Limitation: Pools have boundaries (to prevent exploitation, burnout, or drain).

Exchange: Value circulates through reciprocity, tracked in open ledgers, visible to all.

Here .. there is no single Judas to run away with the purse because the protocol holds the space. There is no single fungus to monopolize the network ... because everyone roots into the system. And no friar must break their vow ... because the system itself becomes the steward.

This isn’t merely about decentralization. It’s about distributed moral coherence. A structure that aligns with care, limits power, and metabolizes resources into well-being ... just like the fungi, just like the forest, just like the friars once dreamed.

We may never escape money’s smell. But we can learn to compost it.

And perhaps this is our task ... not to erase the material world or condemn exchange, but to tend the spaces where value becomes service, where promises become pathways, and where commons are stewarded like soil: with humility, attention, and joy.

St. Francis of Assisi is renowned for his call to "repair my church."

In re-designing our economic systems to be more like ecosystems of connected commitment pools, we may yet recover that deep wisdom: that when we hold value together we don’t just preserve integrity. We repair the commons and ourselves.

Great mediation on the need for objective 3rd parties, and our hope that machines could fulfill that role. In one sense money also plays mechanistic "neutral 3rd party" within commitment pools, because USD or KS are commonly used to help provide a common language of value.

In contrast, asking people to perform the job of neutral 3rd party is often filled with strife, as your example of Judas explores. One reason for that is the failure of Plato's logic: the expert ("philosopher king") is not necessarily the least biased.

An alternative can be found in the wisdom of the crowd. A "jury of your peers" or a scientific journal "peer review" and democratic voting are all cases in which we hope that the wisdom of the crowd will act as that objective third party. And that's why Wikipedia has largely replaced Britannica.

In the broadest sense, commitment pool networks replace the expertise of billionaires ruling the economy -- philosopher kings like Elon Musk -- with an economy ruled by the wisdom of the crowd.